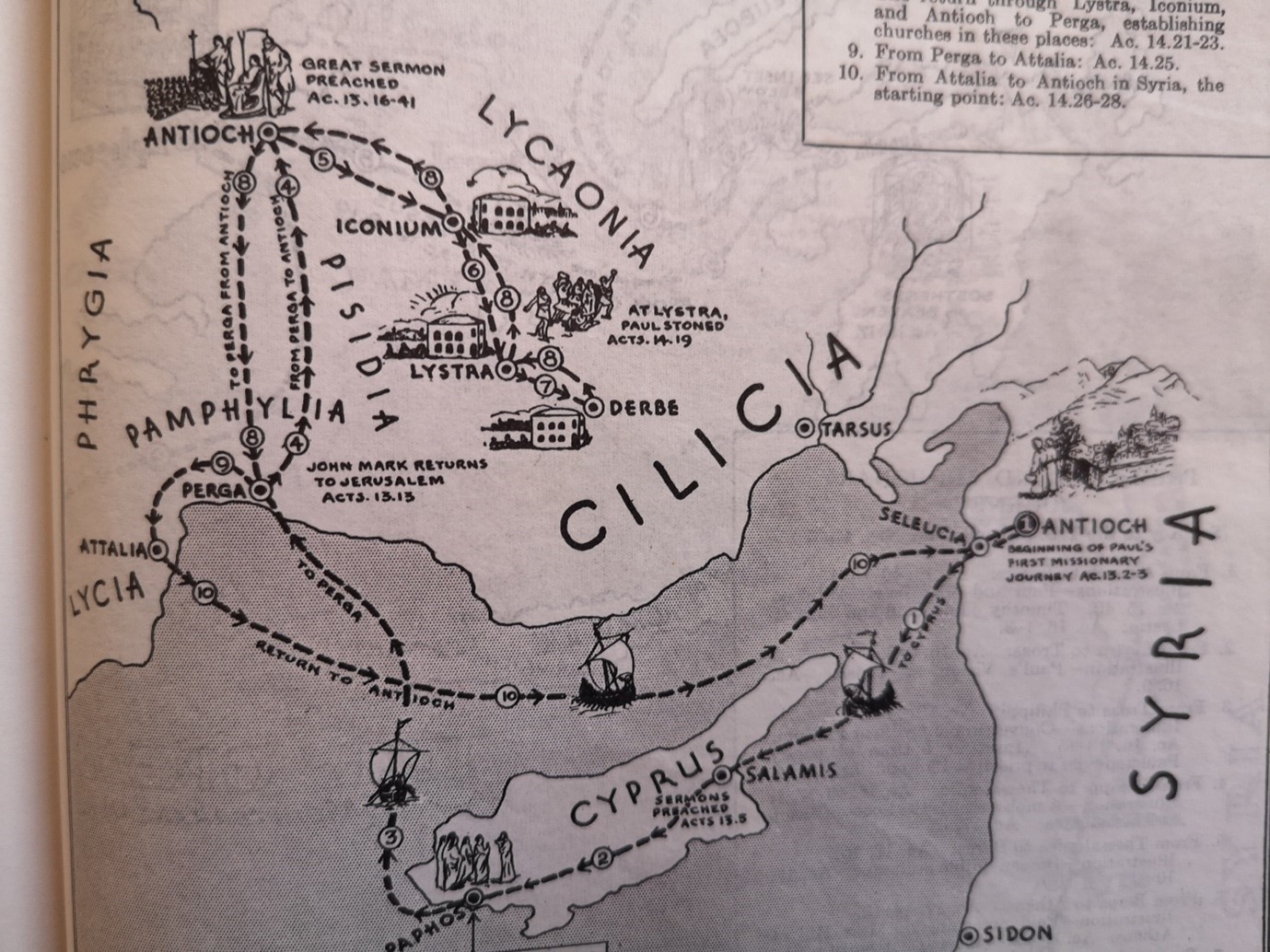

After having 'suffered and been insulted in Philippi',

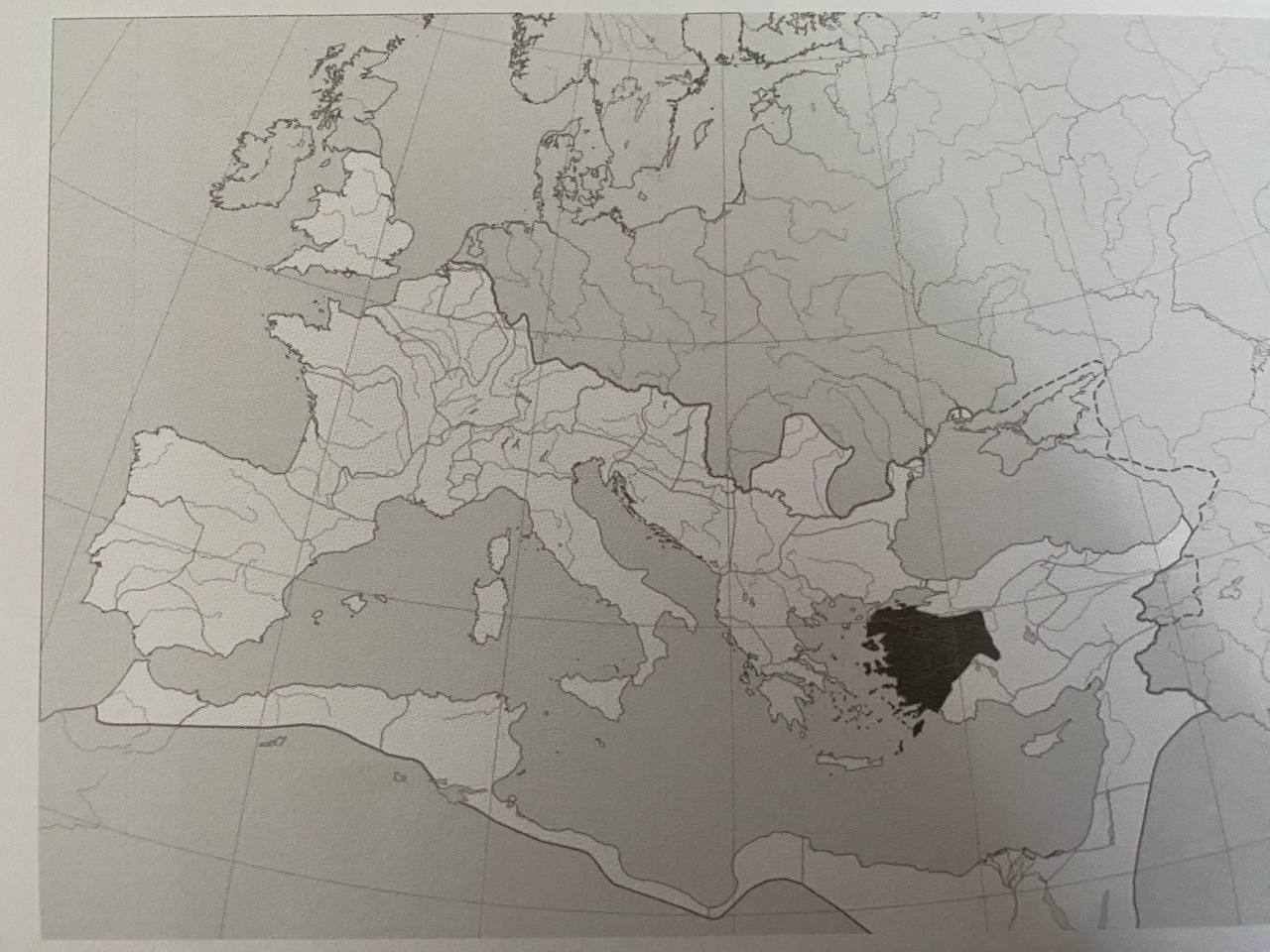

Paul and his co-travellers are off on the 100 mile journey along the Egnatian Road, from Philippi to

Thessalonica.

(map source)

(map source)

Thessalonica was an important town in the area. Positioned on the coast of the Aegean Sea and well placed on the Via Egnatia,

it was a flourishing commercial centre and was proud of its status as a

free city.

This provided certain tax advantages which

assisted its prosperity, so much so that Thessalonica became a prolific producer of coinage.

It had a cosmopolitan population with a large Jewish community - the visit to whom is the subject of this week's study.

Attesting to the importance of the city in the early spread of Christianity, Aristarchus, a disciple of the apostle,

became the first bishop of Thessalonica. By the time of the fall of Rome in 476CE Thessalonica was the

second largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Paul wrote two letters to the new church here, the first of which is reckoned by scholars to be the first written book of the

New Testament.

All texts from the New Living Translation

As seemed to be the norm for Paul, he made for the local synagogue, and spent three Sabbaths in a row where

'he used the Scriptures to reason with the people. He explained the prophecies and proved that the Messiah

must suffer and rise from the dead. He said, "This Jesus I'm telling you about is the Messiah."'.

The response was divided! As always...

Paul's approach here was his standard Christian apologetic towards the Jewish people, following the precedent set by Christ himself.

The Son of Man must suffer many terrible things," he said. "He will be rejected by the elders, the leading priests, and the

teachers of religious law. He will be killed, but on the third day he will be raised from the dead.

Luke 9:22.

The language in v3, "This Jesus..", is a pesher or 'this is that' use of the Old Testament. Paul claims that

the familiar Jewish ideas are fulfilled in the person of Jesus.

His efforts were rewarded and some Jews, along with 'God-fearing' Greek men and 'quite a few prominent women' joined him.

The translation used here is interesting. According to Stott, 'God-fearers' was a generic term for Gentiles, thus Luke

may be referring to four different groups - Jews, Greek, God-fearers and well-known women. The implication, to me at least,

is that the initial preaching in the synagogue went well beyond just the Jewish attendees.

As per usual, the political trouble starts. Some of the Jews 'were jealous, so they gathered troublemakers from the

marketplace to form a mob and start a riot'. They tried to find Paul and Silas, but failed, so dragged their host, Jason

(a Hellenised version of the Hebrew name 'Joshua'), and some others, and brought them to the city council. Luke uses the word

politarchs to descibe these officials. It appears that a body of five politarchs ruled the city at this time.

This was a serious legal problem. It was not a lynch-mob. The rule of law was at work here. Paul and Silas

were advocating an alternative king. Not Caesar but Jesus Christ. This was treasonous. Stott states that v8, often

translated as 'turned the world upside down' misses the mark. Paul and Silas were causing 'radical social upheaval'.

'The verb anastatoo has revolutionary overtones and is used in

Acts 21:38

of an Egyptian terrorist who started a revolt.

In particular, Paul and Silas were charged with high treason'.

Stott goes on to point out the obvious. 'The ambiguity of Christian teaching in this area remains. On the one hand, as

Christian people, we are called to be conscientious and law-abiding citizens, not revolutionaries. On the other hand, the

kingship of Jesus has unavoidable politiclal implications since, as his loyal subjects, we must refuse to give to any

ruler or ideology the supreme homage and total obedience which are due to him alone.' See the discussion questions, below!

The plot follows a familiar path. Paul and Silas leave town. Jason has to put up bail and provide an undertaking

that they would not return. Could this be why Paul states in 1 Thess 2:18 that 'We wanted very much to come to you,

and I, Paul, tried again and again, but Satan prevented us'? They were smuggled out, under cover of night, and

headed off the fifty miles to Berea.

On to Berea.

Again, they head for the synagogue. An unusual phrase appears in v11 in most translations - the people of Berea

'were of more noble character than those in Thessalonica'. Stott remarks, and some other translations concur,

that the phrase 'noble character' could equally well be translated 'open-minded'. I find that nuance interesting!

The Bereans seemed very keen on making Paul work hard for his converts. They were open-minded, but that didn't mean

they'd accept anything. So concerned were they that Paul's ideas matched their understanding of scripture that the very

word "Berean" has come to mean a serious bible student.

Similarly, as in Thessalonica, they had some success. Both with the Jews and, again, "prominent Greek women

and many Greek men".

But the unfriendly Jews of Thessalonica caught up with them (they must have been really annoyed! Why...?)

and Paul was forced to move on, heading off to Athens, leaving Silas and Timothy behind.

With reference to the Bereans, Stott quotes from

Bengel, p662

A characteristic of true religion is that it suffers itself to be examined into, and its claims to

be so decided upon.

-

Paul made straight for the synagogue. Why? Think back to previous studies when Paul did not have

a group of local Jews with which to discuss Christ. What did he do there? Think about the differences in approach.

-

Though the word 'mob' is mentioned in the text, and that might imply a lynch-mob or similar,

it would seem that the accusation against Paul and Silas was rather more

straightforwardly legal. Paul and Silas were pledging allegiance to someone other than Caesar.

What would a modern equivalent of this be?

-

We Brits witnessed the coronation of a new King earlier this

year. I was struck, and disconcerted, by some of the language used in the ceremony. It seemed as if me,

a UK citizen, were to be required to pledge my allegiance to 'my' King. Should I do that?

-

It is still the case in the UK that, in order to be admitted to Parliament, a democratically elected

person must pledge

allegiance to the Crown:

"

I swear by Almighty God that I will be faithful

and bear true allegiance to His Majesty King Charles, his heirs and successors, according to law.

So help me God

".

(Interestingly, there is a version of this oath that does not reference God. However all versions

reference the monarch)

Famously, this means that all correctly elected members from the Irish nationalist party, Sinn Fein, cannot

take their seats - to swear that oath of allegiance

directly contradicts

Sinn Fein's purpose. If you were in

charge of things what changes would you make, if any, to remedy this situation?

-

"I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands..."

...states the US Pledge of Allegiance. This phrase is daily recited by many schoolchildren in the US and, from my

reading anyway, is much beloved by American evangelical Christians. Should it be? Is there a problem with

this pledge? Should a Jesus-follower say such words?

-

Do such pledges matter in today's world anyway?

-

There is a rise in the US of 'Christian Nationalism', a

mashup of American

Christian origin myths with

a rather particular reading of scripture. But surely we Christians should be in favour of merging

the political and the religious? Declare that Christ is the head of the State and require that all citizens

(subjects?) pledge allegiance. What could possibly go wrong?!

-

Look back at the quote from Bengel, above.

- Does your religion 'suffer itself to be examined on'? How do you know that?

-

What specific actions/events can you point to that might prove you had examined your own religion and found

something that needed action, and then acted accordingly?

-

Some Christians are very keen on 'holding true to the faith'. Does that mean they can't change?

What does holding true mean anyway?