| Texts |

| Ps. 132:1-5, Heb. 2:14-16, Heb. 5:1-4, 1 Pet. 2:9, Heb. 8:8-12 |

Before we get to the topic of this week's study can I ask a question? The LSG (and others)

seems to consider it important that we declare Paul to be the author of Hebrews. This, in spite

of the fact that the book states no author and it would seem from an analysis of the

Greek that the author is unlikely to be Paul. Why is it important for some of us to know that

Paul was the author? Does it matter? What do we lose in our understanding of Hebrews if Paul

was not the author?

Read LSG #3: 'The Promised Son' in preparation

for our discussion. You may (almost certainly) find

Jon Paulien's presentation

to the Pine Knoll discussion group to be helpful.

I don't intend to repeat the LSG coverage here. Rather, I'd like to pick up on the overall theme

of the lesson, 'The Promised Son'.

Hebrews 1:1-4 (which is a single sentence in the

original Greek) introduces the 'Son' and makes some strong (and perhaps confusing?) statements about

the position of the 'Son' in relation to the other character in vv1-4, 'God'.

We are all familiar with the notion of the 'Trinity' of 'Father', 'Son' and 'Holy Spirit'. It is

a fundamental belief of almost all Christian denominations, including Adventism

- see Fundamental Belief #2 which states

There is one God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, a unity of three coeternal

Persons. God is immortal, all-powerful, all-knowing, above all, and ever

present. He is infinite and beyond human comprehension, yet known through

His self-revelation. God, who is love, is forever worthy of worship, adoration,

and service by the whole creation.

(Gen. 1:26; Deut. 6:4; Isa. 6:8; Matt. 28:19; John 3:16; 2 Cor. 1:21;

2 Cor. 13:14; Eph. 4:4-6; 1 Peter 1:2.)

But to a typical Jew at the time of Christ the idea of a God who is somehow split into (at least) two

'persons' would be deeply problematic. After all does not the first commandment say "You shall have

no other gods before me" where 'me' is decidely singular? The multiplicitly of gods in the pagan

nations that surrounded Israel was a constant source of trouble. The Jewish God was very insistent on

being a complete and total and all-encompassing singular God. For Jesus to say "He who has seen me has

seen the Father" (John 14:9) is a shocking statement.

- Do we appreciate just how shocking Jesus' claim in John 14:9 would have sounded?

-

I rather like the wording of the Adventist Fundamental Belief on the Trinity, above.

What do you think? Would you re-word it? Re-emphasise certain parts over others?

How do you view the 'Trinity'? You may well be familiar with this image that describes the relationships:

...which does a decent job of explaining the theology.

...which does a decent job of explaining the theology.

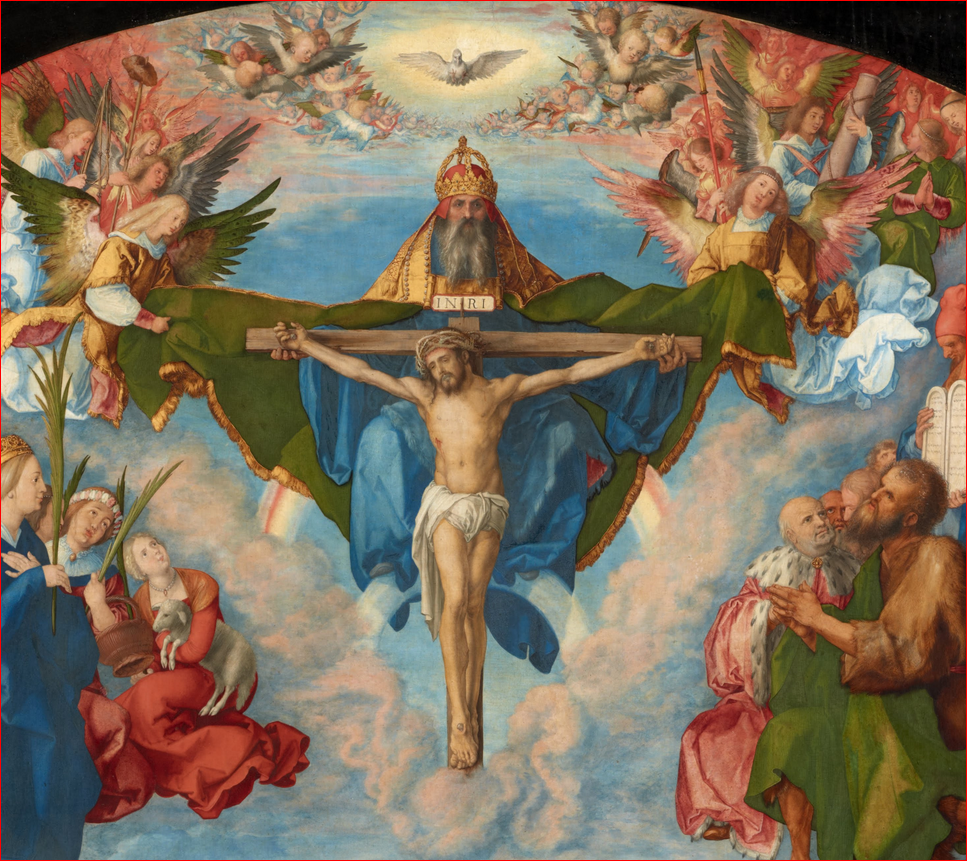

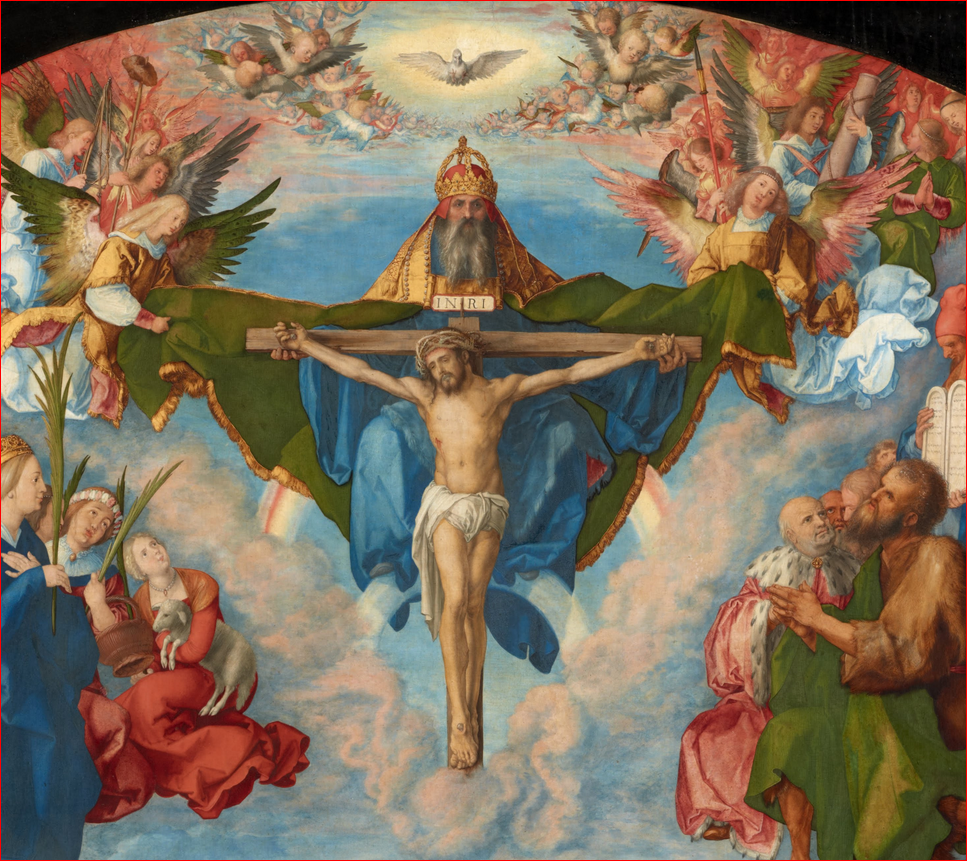

Other representations in art seem to pick up on common themes. God the Father is an old man,

God the Son is the instantly recognisable Jesus, and God the Holy Spirit is a dove. Here's a typical

example - a detail from "The Adoration of the Trinity" by Albrecht Dürer (1511)

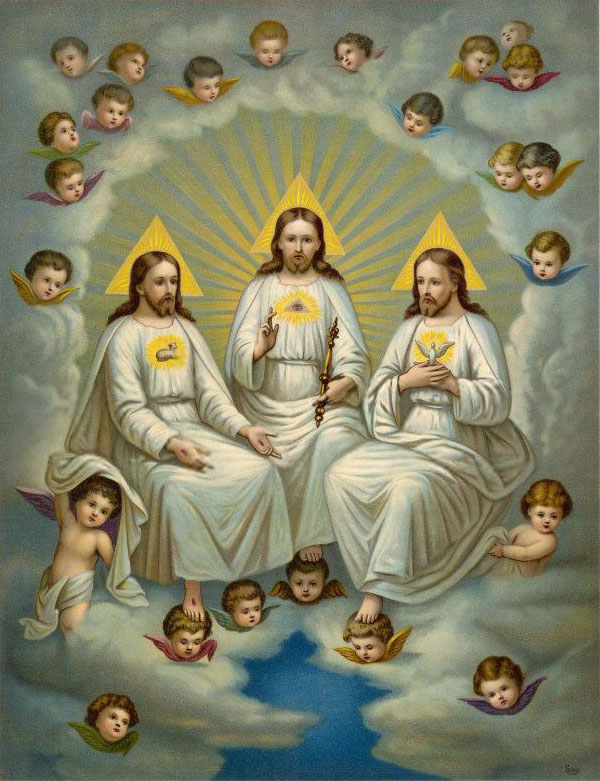

And another from Francesco Alban (around 1640)

And another from Francesco Alban (around 1640)

I always read into such representations an implicit heirarchy. God the Father was in charge, the authority figure. He

was The Boss. Jesus was the sacrifice, the 'soldier sent into battle', younger, somehow one of us in a way that God the Father

wasn't. And God the Holy Spirit? A dove. Some nebulous fluttering flighty thing that does something that we, somehow,

can't quite put our finger on.

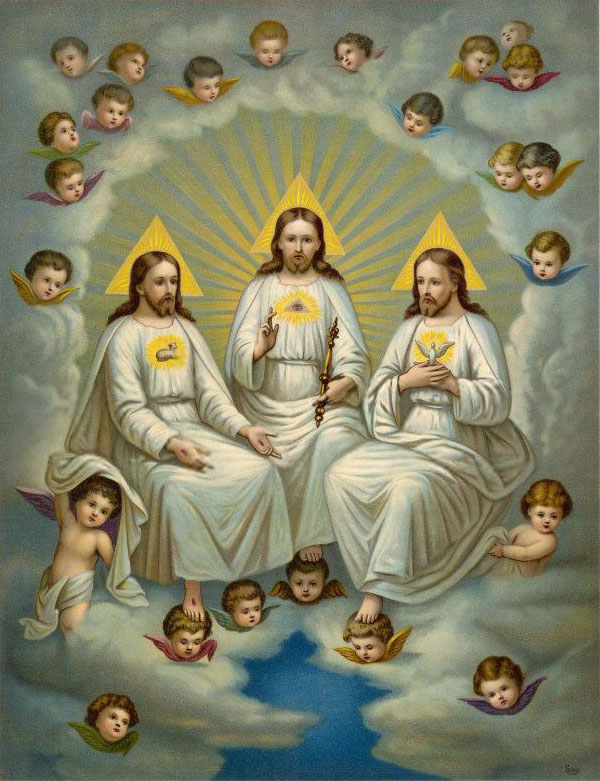

In reading up on the history of the Trinity doctrine in Christian thinking I came upon this rather arresting image from

Fridolin Leiber (1853-1912)

There's all sorts of unsettling imagery in there but maybe it is more accurate in its representation of the Godhead.

What do you think?

There's all sorts of unsettling imagery in there but maybe it is more accurate in its representation of the Godhead.

What do you think?

A thoroughly modern take...

Allow me to wander off a little...

The trinity has often been an extremely divisive doctrine. To some it is plainly and simply heresy.

We are monotheists. There is one God, not three! People have been burned at the stake

for this sort of thing...

You can see the author of Hebrews wrestling with the best way of explaining just who, exactly,

is 'the Son'. Trying to explain that the 'Son' is 'the exact imprint of God's very being' (vv1:3).

God and the Son are the same thing.

I think we, in our modern world have some really rather nice analogies we can use to help us here.

So let's look at two of my favourite things: the

C# computer programming language, and the

wave-particle duality nature of light.

Let's take the second one first - and stick with this! Honestly, it is helpful...

To quote from Wikipedia: Wave-particle duality is the concept in quantum mechanics

that every particle or quantum entity may be described as either a particle or a wave.

It expresses the inability of the classical concepts "particle" or "wave" to fully describe

the behaviour of quantum-scale objects. As Albert Einstein wrote

It seems as though we must use sometimes the one theory and sometimes the other,

while at times we may use either. We are faced with a new kind of difficulty.

We have two contradictory pictures of reality; separately neither of them fully

explains the phenomena of light, but together they do.

Think on that for a bit... There is a real entity called 'light' that seems to behave in two

different ways depending on how you look at it. If the author of Hebrews knew about quantum

mechanics I think he (she?) would find this analogy useful...

To increase the nerd-count of this discussion let's look at the concept of interfaces

in the C# programming language1...

A highly desirable feature of computer code is to be able to hide the details of something away

in code that you need never look at or understand - a concept known as 'black boxing'. All I need

to know to use your black box is what it expects from me and what it will give back. I don't (and

shouldn't need to) care about how your black box does the thing it does.

To put it simply, an interface is a contract. This contract states the behavior of some black box.

It defines the interaction between components that use the interface. It also defines the

interface itself. Most importantly, it leaves out the part about how the interaction is implemented.

Perhaps this is another useful metaphor for the Trinity? I, a human, have - let's be honest - really

no idea how the Trinity actually works. But do I need to? I just need to know

how to talk to 'it' - what does it expect from me and what will it give back?

I've never had a problem with the 'Son' being 'God'. The idea of the Trinity seems quite

reasonable to me and I can't understand why it has been such a divisive doctrine over the years.

But I think that's because I learned my theology in a time when the common language of science

had caught up with the language of theology.

Lucky us!

1 Apropos of nothing, but the website you are currently viewing is

powered by code written in C#...